Late Roman Republic art (200-31 B.C)

During this period, the Romans created their empire outside the Italian peninsula. One of the main consequences of this was the creation of a wealthier elite. At the highest level of Roman society, wealth had its foundation in agriculture. Farming in

the Late Republic became a big operation, required managers, payrolls, and bookkeeping. It was a plantation (latifundia)-based, capital-producing venture.

For the next layer of society—the equites, comparable to the upper middle class—there were more opportunities for wealth accumulation from overseas trade.

At this time, country houses associated with farms became more elaborate. We see the first landscaped gardens with vistas from the Late Republican period. Wealthy equites, who normally lived in townhouses

in the city, began to have vacation villas in the countryside. Small statues, such as the one below, tended to decorate the gardens of the villas of the well-to-do.

Bronze statue of a boar with a hound on its back; 4 ½ inches long; First Century, B.C.; private collection, Great Britain.

Glass

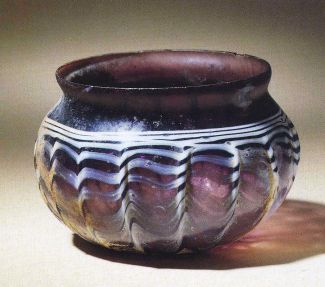

In addition to clay, stone, and metal, the Romans used glass for decorative objects as well as vessels, which were used mostly for ointments. Egypt, not Greece, was the greatest source of glass in antiquity.

Because of increased trade with Egypt and the Near East during the Late Republic, glass-making skills reached a high level. Archaeologists believe that the first objects made completely of glass-paste were

created by the Egyptians in about 1500 B.C. Glass factories have been excavated in Egypt from the Eighteenth Dynasty (ca. 1500). In about 500 B.C., it became popular, particularly in Egypt, to make glass

objects from molds. Most glass from this period was opaque.

Violet colored, hemispherical bowl, ca. First Century B.C. 3 ½ inches in diameter. The rim is slightly flared. Decorated with white lines. Private collection, Great Britain.

Glass-blowing dates from this time, about the First Century B.C. Pliny the Elder thought that the Phoenicians invented glass. His story was that Phoenician sailors encamped for the night, left their cooking

pots on the fire mistakenly overnight. When they awoke, they found glass created by the melding of sand and alkali at a high temperature. But archaeologists have not found glass that pre-dates Egyptian glass

in Phoenicia. Instead, archaeologists believe the Syrians were the first to develop glass-blowing. Before the advent of glass-blowing, glass objects were extremely expensive. Now they could be mass-produced.

During the Roman Empire, the center of glass making moved from the Mediterranean to Gaul and Germany.

The Garland bowl, the only known example, of cast-glass, which uses the ancient Egyptian method of fused-on decoration; 1 ½ inches high; 7 1/8 inches in diameter. First Century B.C. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, NY.

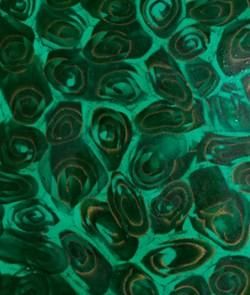

Multicolored (polychrome) glass became the norm in the Roman (and Greek worlds) beginning in the Fourth Century B.C. From about the Third Century B.C., the distinctive multicolored millefiori bowls,

such as the one below, were made in Rome, and around the Eastern Mediterranean for the Roman market. Millefiori means thousand flowers. These bowls were made by fusing glass canes of different

colors and then pressing them into molds.

The Egyptians tended to adopt even brighter colors for their glassware.

The shapes used by the Romans and Greeks for glass were similar to ones they used for pottery.

Millefiori bowl, ca. First Century B.C., 1 ¼ inches high, 5 3/16 inches in diameter, private collection, United States.

Close-up of shattered Roman millefiori glass from about 80 B.C., no dimensions given, University of Sydney Museum, Australia.

Glass pyxis, small container with lid to hold cosmetics, base is flanged, probably Roman, ca. Second Century B.C., 3 ½ inches in diameter, private collection, Great Britain.

Sculpture

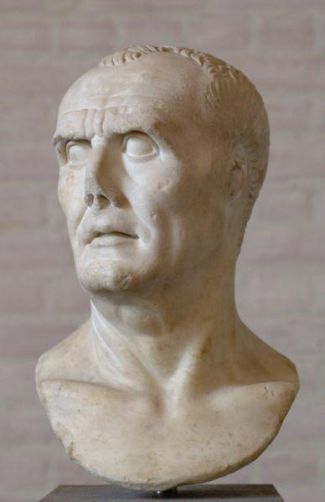

The Romans conquered the Greek states in 146 B.C. This precipitated a migration of Greek sculptors to Rome. Roman collectors greatly admired Greek art. Emperors, and other well-heeled Romans, hired Greek

sculptors to copy older Greek masterpieces. The nobility and the newly wealthy in Rome collected Greek sculpture. When they commissioned their own portraits in sculpture, Greek sculptors were hired to

make them. A golden age of portraiture in stone followed. Without the Roman copies, our knowledge of Greek sculpture would be paltry.

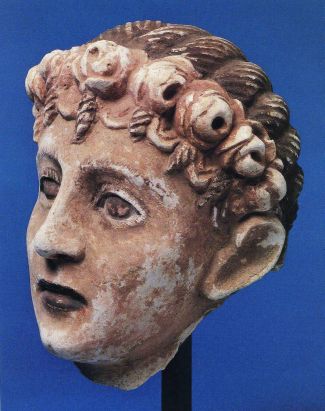

One of the major uses of sculpture was in funerary monuments. In the Late Republic, cremation was still the norm. The custom of burial came from the Near East and supplanted the indigenous Mediterranean

tradition of cremation by the end of the Second Century A.D. However, even the earliest Romans believed in some sort of afterlife. The soul, which lived on after death, was called the manes.

As in ancient Greece, the family of deceased visited the grave and made offerings of drink and food. Throughout Roman history, only the rich had funeral monuments in stone; a modest painted plaster statue,

like the one below, was more common.

Painted plaster funerary head of a woman; Roman, ca. First Century B.C.; 8 inches high, private collection, Great Britain.

After the conquests of Alexander the Great in the Fourth Century B.C., there was increased exposure to marble sculpture and more demand for it, particularly for religious statues. The Romans controlled the

Greek marble quarries at Paros and Thasos even before they conquered Greece. Under the Romans in the Late Republic, new quarries were established on the Mediterranean island Marmara and in Dokimeion

and Aphrodyasias (currently Turkey). The Romans during this time also discovered fine marble in the Apennines.

Bust of Gaius Marius, consul 7 times from 107-86 B.C., anonymous, marble, 16.92 inches high; München, Glyptothek, Staatliche Antiken Sammlungen.

Some scholars believe there was some marble quarrying at Carrara near Genoa during the Late Roman Republic. Most of this marble, however, was used for architectural ornamentation rather than sculpture.

As their empire expanded, the Romans used the distinctive white marble from the Apuan mountains in North Africa and Gaul.

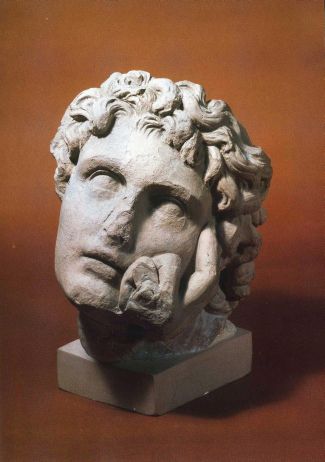

Bust of Gnaius Pompeius Magnus (Pompey the Great) who was granted extraordinary, constitutional powers in 66 B.C.; 9.94 inches high; this is a copy at the Copenhagen, Glyptoteck Carlsbad; original at Museo della Civilta, Roma.

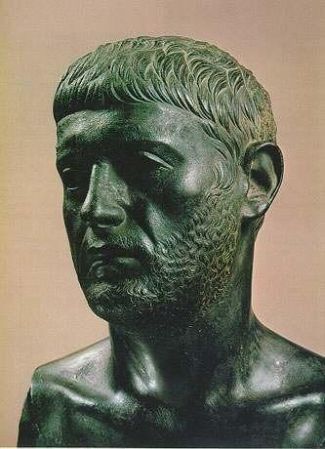

Bust of a Roman man, bronze, anonymous sculptor and subject; 14 inches high; ca. 30 B.C., The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia. Scholars believe that the subject of the sculpture grew his mustache and beard to express grief, this was a Greek custom.

Most of the surviving sculpture from ancient Rome is made of stone or clay cast in molds. The example below is one of the rare statues we have of modeled clay. We can still see a remnant of the so called

“firing skin” particularly on the forehead. Good clay for sculpting was found in the area around present-day Bologna. Many small clay statues have been found in Sicily and Southern Italy. The example

below is believed to be from a tomb.

Head of a youth, Roman, 12 inches high; anonymous; ca. 100 B.C.; Ashmolean Museum, Oxford, U.K.

The late Roman Republic marked the beginning of tremendous demand for Roman copies of important Greek statues. By the beginning of the Second Century B.C., the Romans began making mechanical copies using

the pointing process. A cast was first made of the Greek piece (sculpture or relief). Using calipers and other mechanism to measure, point by point measurements were made. From these marble copies were

made; these copies accurately transferred points from the cast to the marble block. We call the mechanism used a pointing machine from the Italian term for it: macchinetta di punta. Pliny, writing

in about 60 A.D, says that the sculptors Arkesilaos and Pasteles invented this process.

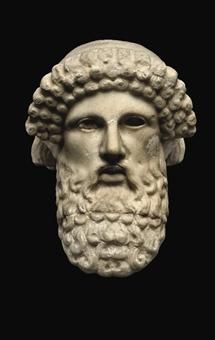

Marble head of the god Hermes, Roman, 8 inches high; ca. First Century B.C., copy of Greek work, which stood at the entrance of the Acropolis in Athens, sculpted ca. 430 – 420 B.C.; private collection, Great Britain. Some spots of plaster repair can be seen, particularly at the upper lip and on the left cheek.

|