Early Roman Republic art (500-200 B.C)

Art of the early Republic was profoundly influenced by the Greek art of Magna Graecia. This was the name given to the Greek colonies in Southern Italy, such as Cumae. These colonies were prosperous during the

period of Etruscan domination of central Italy. In about 400 B.C., threatened by Sicilians and the newly-powerful Romans, the Greek settlements went into a period of disunity and poverty.

Mosaics

One such influence of the Greeks was the use of tiles to create a mosaic on floors. The first of these were from about the Sixth Century B.C. in Magna Graecia in Southern Italy. For floor mosaics, each tessarae (piece of the mosaic) was stone (typically limestone or marble), and they to be completely flat. Wall mosaics were considered the more difficult craft. The documentary evidence of the early Roman Republic suggests

wall mosacists (musearii) were paid more than those who worked on floors. Colored stones began to be used in wall mosaics in about the Second Century B.C.

Detail: Dionysian procession, segment from entrance to a triclinium (dining hall) in Southern Italy; ca. 150 B.C.. Smithsonian Museum of Natural History, Washington, DC

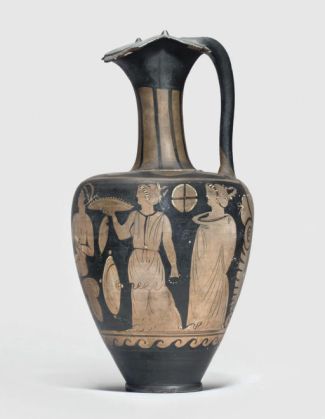

Pottery

The earliest Italian pottery dates from about the Eighth Century B.C. It is of the dark indigenous clay of the Mediterranean. The Etruscans were the first to use the pottery wheel somewhere between 700 and 500 B.C.

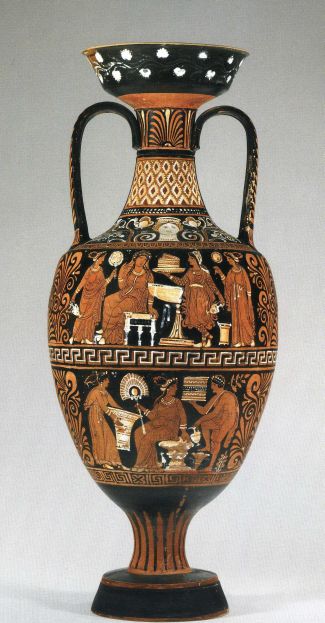

As with mosaics, the Greeks (particularly Athens) deeply influenced ancient Roman pottery types and decoration. Red-figure vases began to be produced in about 450 B.C. During the Fourth Century B.C. several

dominant, independent workshops appear in the following areas: Apulia, Campania, Sicily, Lucca and Paesta.

Campanian red figure vase; attributed to the Rhomboid Group; ca. 320 B.C.; 16 ½ inches high; private collection, Great Britain.

Apulian red figure Lekanis, ca. 350 B.C.; lid has a “Herakles knot,” painted images of female heads; 5 inches high, private collector, United States.

Apulian red-figure Rhyton, ca. 330 B.C.; antlers missing from deer’s head; 9 ½ inches long; private collection, Great Britain.

Another view of the Apulian red-figure Rhyton, above. In this view, you can clearly see the image of the god Eros carrying a patera (flattened saucer used for drinking ritual libations) in his left hand.

The Italian pottery of this period tended to be slightly larger than the Greek prototypes and much more ornate. The red glazes were similar to those used on the Greek mainland rather than in the Eastern Mediterranean,

where more experimentation in glazes was going on.

Apulian red-figure Amphora, attributed to the Patera painter, ca. 340 B.C. Many of the figures are carrying vases, for instance the youth on the bottom right has an oinochoe in his left hand. 31 ½ inches high; private collection, United States.

Sculpture

The Etruscan sculptors took their techniques and subject matter from the Archaic Greeks. Most sculpture was votive and found in tombs. The later Roman sculptors, like their Etruscan progenitors, worked mostly

in terracotta, clay, or bronze. Marble was not widely used until the late Republic.

Votive figure of an unknown deity, earthenware, excavated in Rome, Italy, ca. 200 B.C.; 23 inches high; Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

During the Second Century B.C. Greek sculptors migrated to Rome, the new powerhouse of the Mediterranean region. The recipe for bronze had been known from Minoan times (ca. 3000-1000 B.C.)—one part tin to nine

parts of copper. The main sources of copper in Italy were Etruria, Bruttium and Elba. During the period of Roman domination, Spain was also an important source of copper. Spain was also a major source of

tin, as were Brittany and Cornwall. In the ancient literature, bronze from Syracuse and Campania were particularly valued. But archaeologists have not been able to distinguish these from bronzes originating

in other parts of Italy. Like the Greeks, the Romans used the same word for copper and bronze: in Latin aes, in Greek χαλκóς.

Terracotta Cinerary urn, ca. Second Century B.C., traces of polychrome; 10 ½ x 17 ½ x 8 ¾ inches. Private collector, United States.

Bronze statue of Aphrodite Pselioumene, ca. 200 B.C., After the Fourth Century B.C. statue by the renowned Greek sculpture Praxiteles. This piece is hollow-cast. 5 15/16 inches high. Private collection: Europe.

Following the Greek model, sculptors of the early Roman Republic used wooden models for marble sculpture. The increased realism of late Greek sculpture is reflected in Roman sculpture of the Third and Second

Centuries B.C. Particularly in the depiction of hair, natural looking locks prevail over the formal perfection of previous Roman and Etruscan sculpture. As with the Greeks, the marble was carved in pieces

and folds of drapery were often used to hide the spots where they were joined. The spot where a head was attached to the bust was often covered with the top of a toga or a breastplate.

Portrait of a Nubian, dark gray marble; ca. Second Century B.C.; 11 ½ inches high; Brooklyn Museum of Art, New York.

|